Gemma Arterton knows just how sexist the film world can be. Over lunch, she tells Eva Wiseman she’s fixing her career – then two celebrity fans show up…

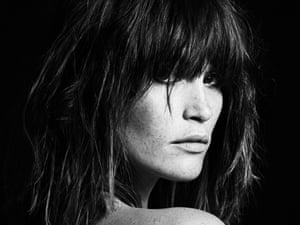

Gemma Arterton in profile looking over a bare shoulder, with dark, straightened hair: in black and white

‘A revolution is happening, but in its own quiet English way. It’s an exciting time’: Gemma Arterton. Photograph: Simon Emmett/Observer

Eva Wiseman

Sunday 18 September 2016 07.00 BST Last modified on Tuesday 20 September 2016 11.45 BST

If you ask Gemma Arterton if she regrets her career choices to date, she will look you straight in the eye and tell you it’s complicated. The year she graduated from Rada she appeared in Guy Ritchie’s RocknRolla; in a Brit comedy with Mackenzie Crook; as the lead in Tess of the D’Urbervilles; and as Bond girl Strawberry Fields in Quantum of Solace. From there, she went straight on to blockbusters Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and Clash of the Titans. On her first day working on Quantum of Solace she filmed her death scene, lying naked for two hours on Bond’s bed, covered in black oil. It seems now that the experience gave her time to think.

It’s a hot afternoon in Soho and she is mixing a drink with the casual swing of someone just home from holidaying with her best friend; she’s tanned, freckled, quick to laugh. At the weekend, for her belated 30th birthday party, she tells me she’ll be performing TLC’s “No Scrubs”. Suddenly she’s rapping. “See if you can’t spatially expand my horizon. Then that leaves you in the class with scrubs, never rising…” And then my hands are clapping, because that’s what happens to your hands when a girl spontaneously raps.

We’re at the Dean Street Townhouse – and the sun has brought out celebrities like rain does snails. At every table is a doubletake. Arterton, her back to the room, seems profoundly at ease with herself, which makes her stories about the anger she suppressed – about her “freak-outs” after bad experiences at work, about her decision to quit films altogether – all the more compelling.

It happened slowly. Once, she remembers, she was working on a film where, apart from the make-up artist, she was the only woman on set. “Everyone just behaved so badly, people were getting fired left, right and centre. It was just power, power, power.” She hated it. “After that, for a while I was doing ‘Fuck You’ work, because I was angry about the industry. I wanted to do these aggressive films to show that I was badass and could kill people.”

I wanted to do these aggressive films to show that I was badass and could kill people

In 2010 she told GQ she wanted to work with directors “who respect me, who don’t just see me as a piece of ass”, a quote which people, including Simon Edge at the Express, took umbrage at, inviting a “leading critic” to respond: “Let’s face it, she’s not getting the Hollywood big bucks because of her acting skills. As far as the studios are concerned she is basically a cheap bit of British totty.”

“So then there was a point, about four years ago,” she says, “where I decided I couldn’t do it any more.”

What is it to be an actor today? To be a star? Talent and skill aren’t enough, nor is beauty, the ability to walk confidently from the sea in a bikini, or the ability to command a room. Nor good reviews. Nor an agent with claws. Your personality must be perfectly calibrated for a viral life. You must share the intimacies of your relationships and dinners online, and build a community of followers, rather than fans. Your quotes must be titillating, but not controversial, you must be at ease in both Hamlet and the Mail Online. Perhaps because she got thrown so far so fast – from a childhood in Gravesend with a welder dad and a cleaner mum, straight to Hollywood, Arterton is only now starting to take control.

Gemma Arterton in The Girl with All the Gifts.

‘A gun-wielding Miss Honey’: in The Girl with All the Gifts. Photograph: Warner Bros

“There was clearly a point where she appeared to take a deep breath,” says film writer Danny Leigh. She’d done Prince of Persia, Byzantium and Hansel & Gretel: “Pretty dire films, probably pretty thankless experiences, and good examples of the assault course a young British actor has to contend with. But specifically, a working-class actor.”

While actors like Keira Knightley and Carey Mulligan stepped straight into serious cinema, Arterton debuted in St Trinian’s. “Young, working-class British actors get funnelled either into soaps or TV drama or, if they make it into films at all, a very specific kind of social realism,” says Leigh. “Culturally they’re seen as not having quite the dramatic heft or range of their middle-class peers. It also feels like it’s somehow more acceptable to treat them as sex objects.”

Arterton then, though successful, was seen as “chirpy” and “perky”, “and all those other grim clichés about working-class young women”, says Leigh. “And it takes a very brave director to up-end that public persona.” It’s interesting, he adds, to look at the films she didn’t do – especially Under the Skin, a film she was dumped from in favour of Scarlett Johansson. Instead of the serious drama Suffragette, she was in the musical of Made in Dagenham. “And one of the awkward things about Suffragette was it clearly aspired to be about the experience of working-class women, but then cast a middle-class actor to do it. I can see that same script with Gemma Arterton in the lead role, and I actually think it would have felt much more eloquent and true,” he says. “She strikes me as far more intelligent than she’s been allowed to be.”

Across the table, Arterton’s accent slips endearingly between posh and not, and she talks with her hands about time passing. In 2010 she married Italian businessman Stefano Catelli. In 2015 she divorced him. She turned down parts, she learned French. It wasn’t until Arterton realised there was another career to be had, where she didn’t have to continue on a path paved with naked corpses, that she returned to film. Smaller films. Producing.

Gemma Arterton with bare shoulders, tanned, with pale pink lipstick and black and silver eye makeup

Facebook Twitter Pinterest

‘I decided to surround myself with people who “get it”’: Gemma Arterton. Make-up: Kim Brown at Premier Hair and Make-up using Bobbi Brown Cosmetics. Hair: Andreas Wild for John Frieda. Photograph: Simon Emmett/Observer

“It was like when you look up and think: ‘Why do I choose such amazing friends and such bad boyfriends?’ It was the same with work,” she says. “I decided to surround myself with people who ‘get it’. Work in a different way. Younger, smaller, lower-budget films.”

Part of that was a decision to speak up. About body image (“Why does [being a size zero] go hand in hand with the acting profession? It shouldn’t”), about pay disparity (“Part of the reason equal pay is not in place is because we are shy to speak up. If we can get companies to publish [figures], we will be able to see for ourselves”) about the whiteness of the film industry, and class, and feminism. Her voice joined a growing hum of voices, questioning.

Gemma Arterton in St Trinian’s in 2007.

Too cool for school: in the film St Trinian’s, in 2007. Photograph: Sportsphoto Ltd/Allstar

In film, people like Geena Davis started campaigning on the representation of women on screen, and the Bechdel Test (“Does this film feature at least two women who talk to each other about something other than a man?”) became widely debated. It was part of a bigger conversation, where women started sharing their stories on social media and in places like the Everyday Sexism project – a shift away from that accepting, heavy silence.

That’s why the question about regret is complicated. Ten years ago, when she was propelled from drama student to star (or “cheap British totty”), Arterton knows she wouldn’t have lasted long if she’d been as outspoken as she is today.

“It was a different time, and not just for me,” she says. “When I started talking about how I didn’t enjoy parts of my job, and talking about body image, I got in trouble. So I stopped.”

But the more crap she saw, the more she felt dismissed, objectified, angry, the more she felt she had to speak out. And today, as she begins to produce her own projects, concentrate on theatre (later this year she takes on the notoriously difficult Saint Joan at the Donmar Warehouse), and turn down big-budget, arm-candy roles, she believes that journey, those shocks, were necessary for her to end up with a career she’s proud of.

“It’s easier to conform and shut up. That’s the way it’s always been with women. Easier than putting yourself out there and having an opinion, to which someone might retaliate. I’m sure there are people who don’t want to work with me because they think I’m difficult – ‘one of those feminist girls’ – but to be honest with you I don’t want to work with them. And that’s fine. Now.”

She finishes her drink. “A revolution is happening, but in its own quiet English way, because people work fucking hard, and it’s hard to live, and everyone’s had enough of being fucked over. Look at Philip Green – people are angry at the moment, and now they’re being encouraged to pipe up. It’s an exciting time.”

Bond girl: Gemma Arterton as Strawberry Fields in Quantum of Solace, with Daniel Craig.

Bond girl: as Strawberry Fields in Quantum of Solace, with Daniel Craig. Photograph: Allstar/Sony Pictures

A head pops round the corner. “Sorry to interrupt.” It’s Steve Coogan. Another. “Hiya!” Rob Bryden. “Gemma, we just wanted to come over, and tell you we’re massive fans, and…” It gets slightly blurry after that. Some mutual compliments, an exchange of banter, cheek kisses, a joke about agents. They leave. Arterton turns back to me, beaming. “Sorry! Gosh. What were we saying?” Still grinning.

There are people who don’t want to work with me as I’m ‘one of those feminist girls’ –and that’s fine

The project she’s promoting today is The Girl with All the Gifts with Paddy Considine and Glenn Close – a raw and stylish thriller, being marketed as a “new kind of zombie film” with the lead a little girl (Sennia Nanua, aged 12 when the film was shot). Arterton was attracted to the story because it seemed, she says: “Particularly relevant at the moment, with immigration and now Brexit. With accepting that the natural way that humanity evolves is by moving about.”

Arterton plays the empathic teacher, a sort of gun-wielding Miss Honey to a zombie-fied Matilda. At one point in the film, the girl asks Considine why humans get to live, while the zombie “hungries” have to die. Is it just because the humans got here first? Plus, Arterton was keen to work with the producer, Camille Gatin. “Camille was telling me that they’d go into finance meetings where the money men would say: ‘Can you make this character into a man? There are too many women in it.’ And she just said: ‘Bye.’”

Gemma Arterton, smiling, with pink lipstick and black and silver eye makeup, her dark, straightened hair framing her face and over one eye

Facebook Twitter Pinterest

‘I know now what I want to talk about, what I want to explore. That’s women’s place in the world.’ Photograph: Simon Emmett/Observer

A screenwriter told me about his experience of sitting with Arterton in a similar meeting, where they were pitching to financiers who, he said, bombarded her with sexist questions. He expected her to walk out – instead, he marvelled, she calmly took the questions to pieces, controlling the room, and leaving with the money. Arterton chuckles when I ask about it. “Sometimes I do feel sorry for modern men.” A camp sigh. “I’m reading this amazing book, All the Single Ladies by Rebecca Traister, about feminism and marriage, and what it means now that, financially, women don’t really need men any more. It’s meeting men like those city boys, though, that makes me want to produce more films with what they call ‘likable characters’. To challenge them.”

Arterton’s excited about a film she’ll shoot later this year, playing a woman who walks out on her husband and child. It’s called The Escape. “Dominic Cooper plays my husband. He and I were talking about how sometimes we look at people back home that got married young and had kids and we envy their lives…” she trails off, grinning. “Sorry – that thing with Steve Coogan and Rob Bryden, that was cool wasn’t it?” Yes. “Are you going to write it in?” Yes. “Oh good, thank you.” She cackles.

If you lie about something long enough you start to believe it

Now that she is moving into producing, Arterton has been given what she calls “the list”. Down one side are the names of actors and down the other is their grade. “It runs from A+ all the way down. At the top are people like Emily Blunt, or anyone that’s been nominated for an Oscar. I’m a B-, which means I’m not that ‘financeable’. My bankability would go up if I did a blockbuster. If only I could be more like Gary Oldman, who bashes them out but quietly, action movies that no one you care about is going to see, but mean you’ll be allowed to do what you want for a couple of years afterwards.”

The more we talk the more bizarre her job seems. “Bizarre for so many reasons,” she says. “Even just the acting part. Because if you lie about something long enough you start to believe it. It starts to become the truth for you. With Saint Joan I’ll have to get myself to a place where I know I’m going to die in a minute, sometimes twice a day.”

One of the ways she’s trying to stay sane, to take control, is by deleting all social media apps from her phone. “I have a friend who’s been told she has to put up more ‘outfit of the days’ and regular pictures of her food because a lot of the casting for film happens on social media. The money people go: ‘Well, they’ve got 3m followers and that actor has only got 1,000, so…’ But I’m determined to do things differently. And that’s only because my earlier career informed me. I know now what I want to talk about, what I want to explore. That’s women’s place in the world. And all the stuff that I’m producing, all the stories that I want to tell next, are about that exact thing.”

Gemma Arterton in Tess of the d’Urbervilles in 2008.

One foot in the past: in Tess of the d’Urbervilles, in 2008. Photograph: Sportsphoto Ltd/Allstar

The waiter needs the table back – we’ve run over time – so we find ourselves on armchairs next to half the cast of Made in Chelsea. In a quiet moment I hear them sighing about having been asked to cast some ‘non-white friends’. Arterton widens her eyes at me with an OMG mouth, and moves her chair for a better look. She sits back, giggling.

Her new career suits her. What’s the next step? “Do you listen to the Guilty Feminist podcast?” She recommends it, especially the episode where its presenters challenged each other to stop trying to be “likable”. Arterton slips into the character of a woman organising a meeting. “Instead of going: ‘Hi, yeah, I don’t know if you remember me, we met like a few years ago? I know you’ve been really busy, you’re doing amazing stuff, wow, congratulations on that! Anyway, whatever, so I’ve got this little idea, and I mean, you’re probably not into it, but I thought maybe we could have a cup of tea, I’m buying! But don’t worry if you can’t…’” She centres herself. Sits up straighter. “Instead, she had to say: ‘I’ve got an amazing idea, meet me on Wednesday at two.’” She throws her hands up, as if: “So simple! This year, that’s going to be me. No apologies.”

The Girl with All the Gifts is in cinemas from 23 September